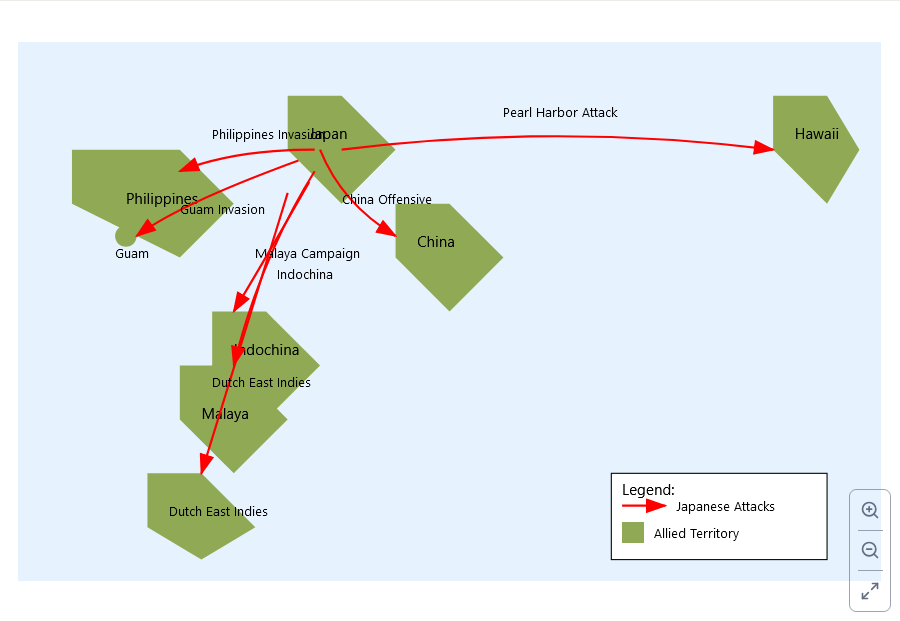

Japan’s December 1941 offensive represented a coordinated series of attacks across the Pacific theater, designed to neutralize American military power and secure access to critical resources. The operation encompassed multiple simultaneous strikes spanning thousands of miles, from Hawaii to British Malaya.

[Source: Author.]

The Pearl Harbor attack began at 7:48 AM local time, with 353 Japanese aircraft launched in two waves from six aircraft carriers. The primary targets were the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s battleships, with secondary objectives including airfields and oil storage facilities. The attack achieved tactical surprise and significant damage, sinking or severely damaging 18 American ships and destroying 347 aircraft. However, the critical aircraft carriers were absent, and the submarine base and fuel storage remained largely intact.

Contemporaneous with Pearl Harbor, Japanese forces launched an invasion of the Philippines. The operation began with air strikes against Clark Field and other military installations, effectively neutralizing American air power in the region. Ground forces landed at Luzon on December 10th, with approximately 43,000 troops supported by naval and air assets. The campaign succeeded in capturing Manila by January 2, 1942, though American and Filipino forces continued resistance on Bataan Peninsula and Corregidor until May 1942.

The Malayan Campaign commenced on December 8th (December 7th in Hawaii due to the International Date Line) with landings at Kota Bharu and attacks into Thailand. Japanese forces deployed approximately 60,000 troops supported by 200 tanks and 560 aircraft. The operation utilized innovative tactics, including bicycle-mounted infantry for rapid movement through difficult terrain. Japanese forces advanced rapidly down the Malay Peninsula, outflanking British defensive positions and capturing Singapore by February 15, 1942.

These operations formed part of a broader strategy aimed at establishing what Japanese planners termed the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.” The immediate military objectives included securing resource-rich territories in Southeast Asia while neutralizing potential Allied intervention capabilities. The operations demonstrated sophisticated planning and execution but ultimately drew Japan into a wider conflict that would exceed its industrial and military capacity to sustain.

The timing and coordination of these attacks reflected careful planning and execution, though post-war analysis suggests that targeting decisions at Pearl Harbor, particularly the focus on battleships rather than infrastructure, may have reduced the long-term strategic impact of the operation. The Japanese operations in December 1941 extended well beyond the major attacks on Pearl Harbor, the Philippines, and British Malaya, encompassing a coordinated offensive across the entire Asia-Pacific region.

In China, where Japan had been engaged since 1937, the December 1941 offensive represented an expansion of existing operations. The Japanese China Expeditionary Army, numbering approximately 850,000 troops, launched new offensives designed to secure coastal regions and prevent China from serving as a base for Allied operations. These operations included an intensification of attacks in Yunnan Province and efforts to secure additional airfields that could threaten Allied positions in Burma and India.

The invasion of Guam, though smaller in scale, represented a strategic effort to secure Japan’s Pacific defensive perimeter. On December 8th, Japanese forces consisting of about 5,500 troops from the South Seas Detachment attacked the island, which was defended by only 547 U.S. military personnel and about 200 Insular Force Guards. The operation concluded rapidly, with American forces surrendering on December 10th, demonstrating Japan’s ability to quickly secure isolated American possessions.

In French Indochina, Japanese forces had already established a presence through agreements with the Vichy French administration in 1940. December 1941 saw the expansion of these positions, with approximately 140,000 troops using Indochina as a staging area for operations against British and Dutch territories. The Japanese 25th Army launched its Malaya invasion from bases in French Indochina, while air units used local airfields to support operations throughout Southeast Asia.

The campaign against the Dutch East Indies commenced in January 1942, following the initial December offensives. Japanese forces deployed approximately 250,000 troops with significant naval support, including the Imperial Japanese Navy’s 3rd Fleet. The operation aimed to secure vital oil resources and followed a methodical island-hopping strategy. Major landings occurred on Tarakan (January 11), Balikpapan (January 24), and Java (February 28). The campaign concluded with the surrender of Dutch forces on March 9, 1942.

The Wake Island operation, beginning December 8th, initially resulted in a rare Japanese defeat when the first landing attempt was repulsed by U.S. Marines and civilian contractors. However, a second assault on December 23rd, with reinforced Japanese forces of about 1,500 troops, succeeded in capturing the island after intense fighting.

Hong Kong came under attack on December 8th, with approximately 30,000 Japanese troops of the 23rd Army facing 14,000 British and Commonwealth defenders. The colony fell on December 25th after fierce fighting, including the defense of Wong Nai Chung Gap and the last stand at Stanley Fort.

These simultaneous operations demonstrated Japan’s remarkable military coordination and initial operational superiority. However, they also revealed the logistical strains of conducting multiple amphibious operations across vast distances. The Japanese military successfully achieved its initial objectives of establishing a defensive perimeter and securing resource-rich territories, but these gains would prove difficult to maintain as the war progressed and Allied forces began their counter-offensive operations in late 1942 and early 1943.

The rapidity and scope of these successes contributed to what historians later termed the “victory disease” among Japanese military leadership, fostering an overconfidence that would influence later strategic decisions, particularly at Midway and Guadalcanal.